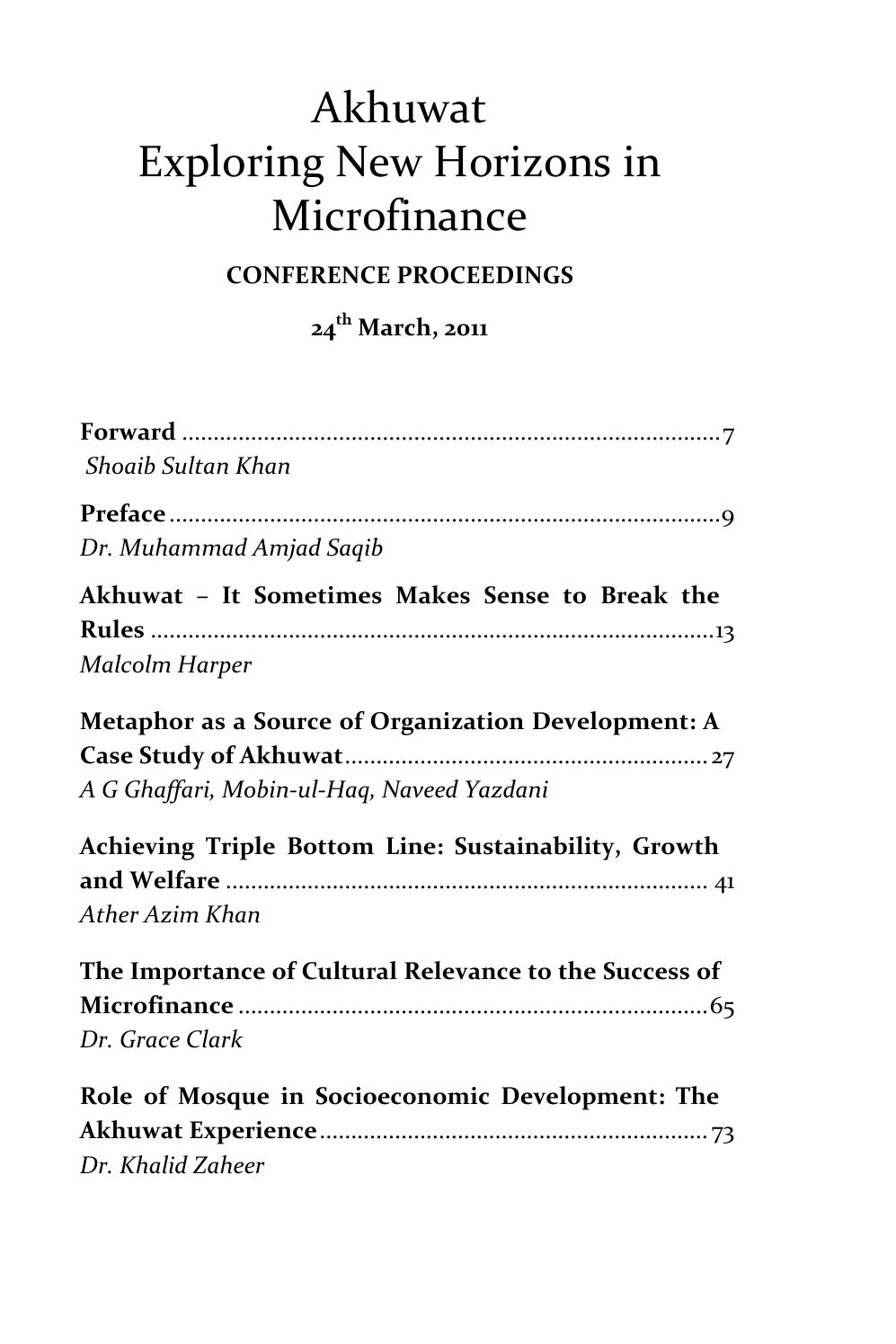

Akhuwat – Exploring New Horizons in Microfinance

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS

24th March, 2011

FORWARD

It was 1998, when I first met Dr. Amjad Saqib, a young DMG officer, who had turned his back on pomp and authority and chosen the path of social mobilization of the rural poor, irrespective of caste or creed, to improve their lot. At the end of five years, when the period of his extraordinary leave to which he was entitled under the service rules, came to an end, Amjad Saqib decided to say farewell permanently to the government job. Since then, he utterly dedicated himself to the service of the deprived segment of the society. This was a courageous and bold step which increased my respect for him beyond measure. He silently, without complaints, suffered when he had given up his service in Punjab Rural Support Programme (PRSP) because of differences with management but did not give up his mission.

In early days of PRSP, when I was at the helm of affairs, Amjad Saqib’s dedication and commitment to improving the situation of rural poor communities, christians or muslims, men or women, left a lasting impression on me of his sincerity and empathy with the poor. In addition, he is endowed with a literary streak which gives his expression the sparkle of a diamond. Sometimes I feel at awe of what he has set out to achieve, but I am confident of his success.

The journey of Akhuwat began in 2001 when a loan of ten thousand rupees was given to a woman. In a span of ten years, this amount has grown a hundred thousand times into a staggering one billion. The achievement of Akhuwat extends beyond the numerology; it lies in the initiation of a movement guided by a unique philosophy that has added new dimensions to microfinance. In an era where microfinance organizations have largely preoccupied themselves with the quest for organizational sustainability,

Akhuwat takes us back to the root purpose that microfinance was intended for; poverty alleviation. This document is a collection of scholarly articles by various experts who offer exhaustive analysis of different aspects of the Akhuwat Model and bring forth the salient features of the model that makes it stand apart from its counterparts.

The journey of Akhuwat is a testament of the ability of volunteerism and self reliance to transform the lives of thousands. It is a story that seeks to inspire and rekindle the faith in the strength of communities and populations to contribute to efforts at poverty alleviation. But most importantly it serves as a reminder of the spirit and objectives which initiated the birth of the microfinance movement. This collection of articles traces the evolution of Akhuwat, reinforcing the distinctive place it occupies as a microfinance institution guided by a unique philosophy which has steered it to reach extraordinary success in a short span of time.

Shoaib Sultan Khan

Chairman,

Rural Support Program Network

PREFACE

To mark Akhuwat’s journey from rupees ten thousand to rupees one billion, an international conference entitled ‘Akhuwat-Exploring New Horizons in Microfinance’ was held at University of Central Punjab. The event brought together eminent scholars and experts who offered exhaustive analysis of different aspects of the Akhuwat model and brought forth its salient features that continue to define Akhuwat’s philosophy and operation. The conference reflected our desire to learn from the past, gain from the knowledge and expertise of the speakers, and continue our journey with a new vigor; a journey of scale, sustainability and impact. To this end, at the conclusion of the conference, it was decided to publish a collection of the essays that were presented by the esteemed speakers.

It is how frequently said that there has been a drastic paradigm shift in the concepts and objectives of the microfinance movement. It has become heavily laden with modern economic rationality causing microfinance institutions (MFIs) to be characterized as business ventures. In popular discourse, we talk of the commercial success of MFIs, treating them as practical solutions to a complex business problem. No doubt such a treatment of microfinance has led the movement to grow but one must be reminded here that growth is neither the sole indicator of success nor is it an absolute measure of socio-economic improvement. Growth is merely expansion; development in the true sense of the term however refers to change. The guiding principle of microfinance must be to inspire a change for the betterment of society. Of course growth entails that microfinance will be able to reach a larger segment of deserving populations, however that alone does not guarantee that it will inspire development or a meaningful change in their socio-economic position.

Thus in prioritizing growth, it is widely believed that microfinance has become more of an economic process or a business venture than a tool for poverty alleviation. This is not to suggest that microfinance has not been successful or that it has become redundant. In fact, given that one third of the world’s population still lives below the poverty line, the need for microfinance is glaringly evident.

The idea of Akhuwat was presented before a group of friends in Lahore Gymkhana ten years ago. As a result, the first interest-free loan of Rs. 10,000 was extended to a widow striving to earn a decent earning through honourable means. By utilizing and returning that loan within a period of six months, she reinforced our belief in the integrity that the poor exhibit when we trust them and respect them. Herein lay the birth of an ideology that founds its inspiration not in economic logic but in the spirit of compassion and generosity of man. “Brotherhood,” the literal meaning of the metaphor ‘Akhuwat’ as derived from the Islamic tradition, remains the underlying philosophy that drives the organization. To us, Akhuwat was the birth of a new chapter in micro-finance; one that looks beyond profitability and works exclusively for alleviating poverty through the development of a mutual support system.

In the early years of Akhuwat, people told us that we were being idealistic, that this experiment would fail miserably. We were repeatedly advised that the idea was neither economically feasible nor would it be able to sustain itself over time. But at every turn, we were overwhelmed by the response of the community. Throughout these strenuous years of struggle, the generosity and compassion of our people have been the most important factors in ensuring the success of Akhuwat.

One of the recurring questions that people continue to ask us is how we ensure the sustainability of Akhuwat’s model. Sustainability of an organization refers to the ability of the organization to endure and conventionally this is achieved through recovery of costs and creation of some additional funds that allows the organization to grow. But we do not charge interest nor are we motivated to gain profit out of this venture. This is what strikes most people who doubt the efficacy of the Akhuwat model. Our answer is that it is through the spirit of volunteerism, the principle of low operational cost and dependence on generosity of the community that Akhuwat has not only sustained itself but is also expanding and being replicated. As a philosophy, Akhuwat cannot fail; if our movement does not succeed, it will not be a failure of the principles and ideals that guide us. The inability to realize our vision will only expose the weakness in our own resolve and commitment to wage this struggle against poverty.

Akhuwat has a unique approach and the essays collected in this volume shed light on the methodology and ideology of the Akhuwat model. The first section of the volume gives an overview of Akhuwat; highlighting the unique features of the model and evaluating the efficacy of its operations. In the second section, authors bring forth the role played by religion in the evolution of the organization and the incorporation of Islamic values and traditions within the model. The third section compiles discussions pertaining to the challenges of growth and sustainability of the Akhuwat model in the present times. The last section explores mechanisms to enhance Akhuwat’s work and gives recommendations for a way forward.

Religious teachings have played a pivotal role in formulating Akhuwat’s philosophy and system but Akhuwat itself has never been a religious organization. In drawing strength from all great religions of the world, Akhuwat’s message is for all mankind. The concept of brotherhood in itself cannot be restrictive; it allows for no discrimination on the basis of religion, cast, creed or ethnicity. Akhuwat stands for brotherhood among all, an ideal which is also reflected in the spirit and essence of Islam and other religions.

I am grateful to the authors for presenting thought provoking and scholarly papers and having contributed to this volume which we hope will bring the message of Akhuwat to a wider audience. We expect that this book will not only serve as an insight into Akhuwat’s work but will also encourage others to join our efforts. The change that Akhuwat seeks to inspire is not limited to improved incomes or reduced poverty levels; it is a change in the hearts of all men and women, rich and poor, Muslims and non-Muslims. It is this change in our perspective, which prompts us to embrace the misfortunate as our brothers that will truly sustain efforts at poverty alleviation throughout the world. Akhuwat is not only a system of microfinance; it is a model of compassion, of social justice and of brotherhood.

Muhammad Amjad Saqib (SI)

Executive Director, Akhuwat

Akhuwat – It Sometimes Makes Sense to Break the Rules Malcolm Harper

Microfinance has come of age and has lost its innocence. It is now coming to be seen as just another business, which makes its profits as and where it can. Microfinance is not the only business to have chosen the poor as it’s preferred ‘market segment’. The late CK Pralahad showed that there are many ways of making profits at ‘the bottom of the pyramid’, and we do not criticise Unilever for marketing shampoo in tiny sachets, or Colgate for its profitable ten rupee toothpaste tubes. We assume that the people who buy these products are satisfied with their purchases, and we do not expect their producers to lose money on their sales to the poor.

Most microfinance institutions (MFI), at least until recently, were started with public interest funds, and with welfare objectives, but they have successfully ‘graduated’ from these limited sources of support. Their promoters argue with some logic that they must make high profits to access equity from profit-seeking investors. They must have this equity in order to leverage commercial debt which they will on-lend to satisfy the credit needs of the millions of poor people who are presently not served by traditional commercial banks. These institutions must also hire qualified and experienced managers; they must also be able to offer competitive salaries, to replace the well-meaning but unskilled voluntary sector staff who may have started the institution.

Microfinance practitioners have also learned many lessons (although perhaps not enough), and a body of ‘best practice’ has grown up. Not every institution adheres to every practice, but it is generally accepted not only that they must be ‘sustainable’, that is profitable, in order to survive and to attract and retain investors, but that MFIs should lend through some form of group mechanism, that they should lend mainly to women, and that they should make rather high charges, not only to be ‘sustainable’ but also to discourage misuse of loans, to encourage repayment and to ensure that their loans are not ‘hijacked’ by those who are not needy, as so many subsidised goods and services are.

This paper describes some aspects of the operations of Akhuwat (meaning ‘brotherhood’), an MFI which operates in Lahore and elsewhere in Pakistan. It was started in 2001, its present portfolio is around two million dollars, lent to some 30,000 clients, and its cumulative disbursements amount to about ten million dollars, which has been lent to almost one hundred thousand clients, and it is growing quite rapidly.

Akhuwat is unique because it breaks just about all the generally accepted rules of microfinance, but has nevertheless (or perhaps for that reason) survived and grown. In the present crisis of opinion and reputation which is swirling around microfinance, not only in Andhra Pradesh and India, but globally, Akhuwat is a lively proof that there is ‘another way’, which may also be a better way.

Akhuwat is not as large as the largest for-profit MFIs, but it is large, and growing; it has long passed the stage where it might have been dismissed as the dream of an idiosyncratic idealist. It is a large going concern, reaching towards a client base of one hundred thousand people, and it has also been widely copied.

WHY IS AKHUWAT SO SPECIAL?

INTEREST

First and most obviously, because its loans are interest free. There is endless debate about the meaning of ‘usury’, or riba, which is condemned in both the Christian Bible and the Holy Koran; does it mean ‘excessive’ or ‘unreasonable’ interest rates, however those imprecise terms might be defined, or does it mean any kind of fixed interest charge, a cost for the use of the money, even one which is levied to cover the bare administrative costs of the lender, or to compensate for the loss in the value of money over time which is caused by inflation?

One way to avoid this dilemma is to adopt one of the profit sharing modes of Shariah-compliant finance, such as musharaka, or mudaraba. Or, more understandably in the West, ‘venture capital’, or ‘equity’ investing, where the person or business that has been financed shares its profits with the institution which provided the finance. These methods are never easy; the prospective profit shares of each party have to be negotiated at the time when the investment is made, and the precise definition and calculation of the profit from a single transaction or from a business as a whole, are complex and fraught with potential for disagreement.

There are many well-known venture capital investors, some of which have taken stakes in microfinance institutions, but they rarely take stakes in start-ups, or ‘ventures’. They should more correctly be called ‘development capitalists’, who invest substantial sums in business which have survived their earliest years and have proved that they can make profits. The ‘transaction costs’ of such investments are high even in relation to the several millions of dollars which are invested.

There have been a few isolated attempts to apply profit sharing methods to microfinance.1 These have generally foundered, or have remained very small, because of the issues mentioned in the preceding paragraph.

Larger businesses do at least keep records of their profits, even if they are not always accurate. Many of the microentrepreneurs who are served by microfinance are illiterate, they do not separate their personal incomes from the profits of their tiny businesses, and it may even take longer to figure out what their profits may be in the future, and are at present, and how to share them, than it does for a multimillion dollar business with audited accounts. If the investment is as little as $100, or even $1000, the transaction costs may exceed the amount invested. There are other sharia compliant financing methods, such as mudaraba sale and leaseback, but I hope I will be forgiven for my sense that these adhere to the letter of ‘no fixed interest’ but not to its spirit.

Hence Akhuwat has chosen what may be the only totally genuine way of avoiding interest or other disguised charges; they make no charges at all. Initially, Akhuwat levied a flat fee of five per cent to cover some of its administrative charges; this was of course very low, except for short duration loans, and it did not cover of all Akhuwat’s very low costs. After a few years, management decided to be completely absurd, to stop levying any charges at all. This may appear crazy, the antithesis of ‘sustainability’, but Akhuwat is still alive and well, when other MFIs have disappeared, and many others may do likewise in the next few months, while Akhuwat is growing, fast. How has this been achieved?

The answer lies in the name; Akhuwat, brotherhood, looking out for those who are less fortunate than yourself. Even before Akhuwat abandoned the five per cent charge, some clients had made voluntary contributions to its costs, in gratitude for their assistance. I myself met one such person in Lahore. He was a small mechanic; a loan from Akhuwat helped to expand his business, he used the profits to finance a trip to the Gulf, and had returned relatively well-off; he felt that it was only right to contribute something to allow Akhuwat to do the same for others.

This system has now been formalized, and clients’ voluntary contributions cover about sixty per cent of Akhuwat’s operating costs. The borrowers contribute what they can; those who have been successful give more than those who have not, and some give nothing; there is no compulsion, moral or otherwise, and clients who have made donations are treated no differently from those who have not when decisions are being made about new loans.

For this reason alone, Akhuwat is unique, but there are many other features which make it an ideal, and also a model from which others can and should learn, irrespective of their religion or other motivation.

SOURCES OF FUNDS AND OF LABOUR

Akhuwat is the final link in a value chain of generosity. Its funds are donated, from all manner of sources, large and small, rich and not so rich; those who give their money in this way clearly feel that this is a more productive way of helping poorer people than giving them grants or doles. The funds are recycled, the same sum can continue to help people forever, subject only to inflation, and Akhuwat’s recovery rates are as high as any ‘normal’ MFI.

One major argument for charging interest, and high interest at that, levied according to the period for which the loan is not repaid, is the fact that borrowers will obviously repay faster if the amount to be repaid increases over time. What is more, they will be ‘economic women, and men’; they will tend to repay the most expensive loans first, and to delay repayment of the cheaper ones.

Akhuwat’s performance gives the lie to this statement of obvious economic common sense. Its loans are the cheapest, in fact they cost nothing at all, but they are still repaid on time. Its on-time repayment record is about ninety-nine percent.

Conventional wisdom may be overturned in this case, but Akhuwat’s choice of sources for its funds seems even more foolish. It might have been possible to raise some donations at the start, but is it not irresponsible to build an institution on which its clients will depend on such an unreliable and unpredictable source of funds? Experience so far suggests otherwise; Akhuwat has until very recently taken no official foreign grants at all, and the only grant of that kind so far has been a capital sum to finance expansion to a new area. Akhuwat has also avoided taking ‘official’ local funds; they have relied entirely on individual donations, large and small, from clients, from well-wishers and from all manner of other sources.

Can this be ‘sustainable’? Will the funds keep on coming? Commercial loans and investments are not themselves wholly reliable, as we all found in the recent financial crisis, and as many businesses and individuals of the kind who are assisted by Akhuwat have always found.

But human generosity seems to continue. There are now over one hundred ‘micro-finance investment vehicles’ or ‘MIVs’. Most of them are financed by wealthy individuals and institutions who are not wholly profit maximisers, who want to ‘give something back’, who are looking for below market returns in order to do more than make more money.

This sacrifice is in itself generous, and the managers of these funds are now searching hard for effective ways to measure the social impact and poverty outreach of potential investee MFIs; they want to reduce their profits in order to do more good.

These are investors who want to preserve their capital, and to receive a sub-optimal and modest return on it if they can. They are already started on the slippery slope down, or perhaps up, towards straight giving, even though some of them are in some sense embarrassed by their own behavior, and are anxious to portray themselves as hard-nosed capitalists; ‘brotherhood’ lurks in all of us, as Akhuwat has found.

The international aid world is embarrassed with funds, both private and public, and donor agencies’ main concern is often to ‘move the money’, in order to achieve their spending targets. There are many reasons why people donate to Christian Aid or to Islamic Relief, or willingly pay their taxes to DFID or USAID, but we must not be too cynical. Generosity, brotherhood in the broadest sense, has a great deal to do with it. People keep on giving, rich and poor people, NGOs and governments, and the flow of such funds is probably as reliable as the flow of commercial funds. Akhuwat has designed a unique value proposition for those who want to get the biggest ‘bang’ for their donated ‘buck’, and there is no reason why this should not continue.

It is quite easy to give money, even if you do not have very much, but it is much harder to give time. Not an hour here or there to attend a committee meeting, to talk to a group of children or to organise a fund-raising event, but regular time, just like paid time, except that it is unpaid. Akhuwat has also successfully mobilized this source of support. This is in part due to the remarkable example of Akhuwat’s founder, but it also comes from the same natural generosity, the spirit of brotherhood, that encourages donors to give money.

Many of Akhuwat’s senior staff are volunteers, and most are paid far less than they could earn elsewhere. Only the junior staff, who are mainly drawn from the same communities as the clients, are paid the ‘market’ rate for their work. They too tend to work harder and for longer hours than they would elsewhere; they also become infected with the dangerous spirit of brotherhood which pervades the whole institution. The market, for money, for labour and for skills, need not always be the king.

THE CLIENTS, THE PRODUCT AND ITS DELIVERY

Group intermediation is almost axiomatic in microfinance, outside Latin America and Indonesia. The groups may themselves borrow and then on-lend to their members, as in the Indian self help group model, or the groups may only be ‘social’ intermediators, as in the conventional and widely replicated Grameen Bank approach, where the groups appraise and approve each others’ loans, and assist with recoveries, and, in some cases, act as guarantors for their fellow members’ loans.

Similarly, and for related reasons, microfinance is everywhere dominated by women. There are good reasons for this; women are generally the poorest and most marginalized members of society, and they can be ‘empowered’ to improve their situation through group membership and by having some control over small sums of money. Women also work better in groups than men do, and they are weak and have fewer options; it is therefore easier to put them and keep them in groups, and to ensure that they repay their loans.

There are also some reasons why it may not be so good to work in groups, and exclusively with women. Groups tend to discourage and even to crush individualists, and entrepreneurs are above all individualists. Group guarantees are inequitable if some members want to borrow more, or more often, than others; groups tend towards the lowest common denominator.

Women are more than half the population, and in most societies and activities their skills and entitlements are woefully neglected. The family, however, is the basic building block for most societies, and families include women and men. Discrimination in favour of women can have its downsides; men may force their wives to take loans and to repay them, but then use the money for liquor or other amusements, and the family disharmony can end in disaster. Anyone who has seen a Bangladeshi woman’s face which has been foully disfigured by the acid which was thrown at her by her frustrated husband will be aware that family unity should be enhanced, not destroyed.

Men also tend to start more business that eventually grow and employ many others, than women, but they also tend to take bigger risks, to be less reliable, and to fail more often. Both sexes have their roles to play.

Akhuwat started with groups, and still uses them in some particular cases, but the main customer unit is the household, the wife and the husband. Both co-sign their loans, and are responsible for repayment, and the household also takes a guarantor, who is usually also an Akhuwat client. The guarantors are themselves not allowed to borrow until the loans which they have guaranteed have been fully repaid.

For this reason, some borrowers prefer a more traditional group system, and Akhuwat has recently re-introduced group borrowing to satisfy them; prospective borrowers can chose whether to take a guarantor, or to join a group.

Here again, Akhuwat’s practices fly in the face of accepted best practice, but they achieve good results. Any MFI can learn from them, whether its goals are to make big profits, or to create a ‘big society’.

Akhuwat has another unusual strategy which saves money and also strengthens commitment and the sense of brotherhood. Loan repayment and disbursement takes place in mosques, or churches, not in Akhuwat’s own very modest offices. Jesus Christ threw the money changers out of the temple in Jerusalem, saying that they had made the house of God into a den of thieves, and some of them may indeed have been money-lenders also. Akhuwat may be accused of being foolish, although its results tell otherwise, but it is certainly not a thief.

These meeting places involve no cost, because they are not needed for worship at the times when Akhuwat uses them, and they confer a sense of solemnity which surely enhances borrowers’ commitment to repay. The priests and imams also welcome Akhuwat as a bridge between people’s spiritual and secular lives. The Holy Koran says that money is given to us in trust, to be used wisely and then handed on to others; a loan which has been received and acknowledged in a place of worship is probably more likely to be viewed in that light than one which is taken in a banker’s office.

THE PROCESS– ‘GRADUATION’ AND REPLICATION

Most MFIs are businesses, and businesses do not like to lose their best customers, or to discourage them from buying more of what the business sells, and to keep on buying it. Hence, MFIs encourage their clients to move up the ‘loan ladder’ to borrow larger sums, and to keep on borrowing. Some MFIs even expel customers who repay a loan and then do not take another within a set period, usually a month or so. They are permitted to ‘rest’, as the MFIs call it, for this period, but then they have to get back into debt, or get out. This is a sensible business practice, because non-borrowing clients are unprofitable.

Akhuwat adopts a very different policy. It is understood that clients are being helped to become better-off, and that they should ‘graduate’ to regular banks as soon as they have outgrown Akhuwat’s scale of lending. Akhuwat’s staff make every effort to introduce such clients to banks, and to facilitate the transfer, and only a very small number of larger so-called ‘silver’ loans are approved, for special cases.

In general, Akhuwat aims to ‘process’ its clients to ‘mainstream’ banking, not to retain them for its own profit. It is a school which prepares people and helps them grow for larger things, not a prison which retains them in perpetual indebtedness. Akhuwat has lent to 93,000 people in the ten years of its existence, but now only 30,000 are borrowing. The remaining 63,000 have ‘flown out’, that is, they no longer need credit from Akhuwat or they have ‘graduated’ to banks from where they can borrow larger sums, or they have ‘dropped’ out, because they failed to repay on time and were not allowed to borrow again. Brief visits to a sample of ex-borrowers suggested that around one on five would like to borrow from Akhuwat again but cannot, and the remaining eighty per cent do not need to borrow.

Most institutions of all kinds like to grow, as Akhuwat has grown and is still growing. Growth enables more people to benefit from their products and services, it enhances the ego and reputation of their founders and it also enables promoters and investors to make more money. Growth is often hard to manage, and it involves losing the ‘personal touch’ which comes from association with particular communities. But the mantra is that businesses must grow or die, so grow they do, and sometimes die in the process.

Here again, Akhuwat is different. It has grown and is still growing in Lahore, its birthplace, but it has adopted two different approaches to growth beyond Lahore. In some towns, local groups are willing to sponsor new units. They are encouraged to do so, using the Akhuwat name, and Akhuwat works with them to show them what has to be done, it sends its own staff to assist them in their initial efforts, but then they are encouraged to move forward on their own, to develop their own approaches and solutions, to be local successes, rather than branded clones of Akhuwat itself.

In other places, where suitably committed people do not come forward, Akhuwat grows in a more traditional way, by opening its own branches. This dual track approach does not maximise Akhuwat’s earnings, but it does maximise the extension of what Akhuwat is doing. Akhuwat’s concern is not to grow as large as it can; it is to succeed in its mission, to bring its services and its spirit of brotherhood to as many people as possible.

There are of course a number of challenges; some are similar to those which face any microfinance institution, while others relate to Akhuwat’s unique business model.

Generosity is probably as ‘sustainable’ as the market, but it is not always as predictable, and this makes it difficult to plan future developments. Because so many of the senior staff are volunteers, the management structure is less hierarchical than is usual in South Asia; the informal trusting culture of Akhuwat is in many ways more like that of a hi-tech start-up in California, and some managers themselves find this difficult.

Clients often complain that Akhuwat’s loans are too small, and demand naturally exceeds supply. This in itself ensures that clients are not encouraged to become over-indebted, which avoids some of the difficulties which have caused so many problems in Andhra Pradesh in India, and it also encourages clients to ‘graduate’ to banks when they have outgrown the scale of credit that Akhuwat can offer. This is not always easy, but it is in Akhuwat’s interest to help its clients to do this, so that Akhuwat’s funds can be used to assist clients who are further down the ‘ladder’ of growth.

In a very broad sense, Akhuwat is itself a paradox. It depends on the generosity of people who have made their money in the ‘greed-based’ market system, but is at the same time promoting a quite different model. If this model was universally adopted, there would be no surplus funds for Akhuwat. This possibility is however somewhat theoretical, and very remote. For the foreseeable future, Akhuwat should be able to access generous people’s funds, and skilled people’s time, and to continue to grow and to demonstrate new possibilities.

CONCLUSION

Microfinance is becoming a mature industry, with set principles and practices. It is also moving away from government and NGO, into the hands of real businesses; it has been ‘Wal-Martised’.

Akhuwat is supremely important because it reminds us of what we set out to do, and why we did it. Akhuwat takes us back to the early days of innocence, when poverty alleviation was what microfinance was for, and this reminder is healthy, and necessary.

At the same time, however, Akhuwat is breaking the mould, and is one of the most important innovators in microfinance, anywhere. Anyone who is setting up a new MFI anywhere, with whatever motives, should at least question the accepted wisdom of working with groups, client retention, focus on women, and approach to growth. The conventional practices may still be the correct ones in some circumstances, but Akhuwat shows that there are other ways, which can work equally well or better.

Above all, however, and most significant in these marketdriven times, Akhuwat demonstrates that there is another way, that generosity and brotherhood can be equally powerful motivators as profit maximisation. This conclusion goes far beyond microfinance.

NOTES

1 See Harper M, “Islamic Partnership Financing for Small and Microenterprise”, Small Enterprise Development, Vol. 5, No.2, 1996, and Harper M, Rao DSK and Ashis Kumar, Development, Divinity and Dharma, The Role of Religion In Development Institutions and Microfinance, PA Publications, Rugby, 2008

Metaphor as a Source ofOrganization Development; A Case Study of Akhuwat

A G Ghaffari, Mobin-Ul-Haq, Naveed Yazdani

To understood using the concept of metaphors. The purpose of this article is to determine how and to what extent an organization can be article seeks to explore and understand the impact of metaphors in the development of an organization’s culture, structure, internal and external communications and its impact on overall performance. This study is conducted on a microfinance organization operating in Pakistan by the name of “Akhuwat” (brotherhood). The very word “Akhuwat” is a metaphor in Islamic tradition and has a deep historical and religious meaning. Using the concepts of modern organization theory, we seek to understand whether this metaphor has any impact, whatsoever, on this organization.

INTRODUCTION TO AKHUWAT

Akhuwat was setup in 2001 as a microfinance NGO offering interest-free credit by a group of people who shared an interest in poverty alleviation and improving the quality of life of the poor and destitute in Pakistan. Akhuwat started its function with a model based on the Islamic tenets of muakhaat i.e., brotherhood and qard–e–hasan. The model was distinctively different from all existing models in the field of microfinance. Akhuwat is a glaring example of departure from tradition, whereby it has so far defied the widely practiced ‘golden’ microfinance principles. Malcolm Harper (2008)1 acknowledged the unique contribution of Akhuwat and said that “Akhuwat is already doing for conventional microfinance what Professor Younas did for conventional banking in the late 1970s.”

The first loan was given to a woman and the successful return of the first loan convinced the friends of the viability of the model and it was named Akhuwat, the first Microfinance Institution (MFI) based on the concept of qarz-e-hasan and zero interest rate. Soon the equity started to grow and people after hearing the methodology and success started to entrust Akhuwat with more and more donations. The rise in donations and the sense of responsibility led the group to evolve a novel organizational structure revolving around volunteerism, values, and lowcost operations. The group of friends turned into the first Board of Governors [BoG] and voluntarily took the responsibility of looking into the strategic and operational issues of significance to Akhuwat. The idea was to discharge societal responsibility by bridging the gap between haves and have-nots and to financially and socially support the needy and deserving and so help them get out of the vicious trap of poverty and debt.

In the last ten years of its existence, since its inception, Akhuwat has shown unprecedented growth; from serving one female with Rs 10,000/- only in one district to extending loan to 100,000 families to the tune of one billion rupees in more than 20 districts of Pakistan with a loan return rate of 99.85%. The success of the organization is not only due to the untiring efforts of its founder Dr Amjad Saqib and its BoG but also owes to the fact that the whole organization embodies the concept of Akhuwat in every sphere of its operations. The concept has proven to be so powerful that it has transcended the organization’s boundary and has taken its roots in the hearts of the community it serves, bonding them strongly with the cause of the organization. For the first time in the history of microfinance the poor, one who took a loan, has become a donor. A miracle that was possible solely because of the metaphor, “Akhuwat”.

AKHUWAT: ITS MEANING AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The very name “Akhuwat” draws its roots from the core Islamic belief of ‘Muakhaat’ i.e. ‘brotherhood’, a term central to the culture of Muslims which represents the sense of love, belongingness, and sacrifice. Islam declares that all Muslims are brothers to each other and many sayings of the Holy Prophet (PBUH) highlight the significance of this notion. ‘Brotherhood’ was witnessed at its zenith in the history of mankind when Muslim immigrants called the ‘Muhajirun’ from Mecca were hosted by their Muslim brothers called the ‘Ansaar’ or ‘Helpers’ in Medinah, on the call of the Holy Prophet (PBUH), who said, “All Muslims are brothers of each other.” “Our Muhajir brothers have left their homes in Mecca. They have given up everything they owned for the sake of the Almighty Allah swt. I want each Ansaari to accept one Muhajir as his real brother,” he said. In response to the call, each of the Ansaar adopted a Muhajir as his brother and said to his Muhajir brother, “You have an equal share in everything that Almighty Allah has given me. Almighty Allah will bless me and my property if you will share it with me.” The brotherhood of the Ansaar and the Muhajirun was termed as “Muakhaat”. This act of Muakhaat is also reflected in the Holy Quran: “Those who believed, and adopted exile, and fought for the faith, with their property and their persons, in the cause of Allah, as well as those who gave (them) asylum and aid – these are (all) friends and protectors, one of another…” (Chapter 8: Verse 72). Dr Amjad Saqib talks of the universal meaning of ‘brotherhood’ as envisaged by Imam al-Nawawi in his famous work “Arba`în of an-Nawawi”, in which Imam anNawawi views that Akhuwat [ukhuwwa] in the saying of the Prophet (PBUH) pertains to bani Adam (i.e. of all humanity).2

The concept of Akhuwat is clear, very strong and dearly held in Islam. All Muslims accept and try to practice this concept in their everyday life. It is this concept that makes Muslims all over the world brothers to each other, making them one nation. Love for each other and sacrifice is at the heart of this concept. Hence, when used as a metaphor it embodies the whole meaning and communicates the same without much effort. The simplicity and clarity of this concept makes it easy to communicate and draw inferences from. It even allows people to judge the performance and policies of the organization. Since it is an everyday phenomena, a dignified value to hold, and a noble practice to indulge in, the metaphor of Akhuwat has the power to shape an organization’s structure, culture, strategy, communication, etc and as such all this makes this metaphor –Akhuwat— ripe to study in the organizational context.

ORGANIZATION THEORY AND METAPHOR

Organization theory helps us in the study of organizations from multiple viewpoints, methods, and levels of analysis. Organizations could be studied at the “micro” level also called organizational behaviour — which refers to individual and group dynamics in an organizational setting — and “macro” strategic management which studies whole organizations and industries, how they adapt, and the strategies, structures and contingencies that guide them.

Organization studies pertain to the study of individual and group dynamics in an organizational setting, as well as the nature of the organizations themselves. Whenever people interact in organizations, many factors come into play. Modern organization studies attempt to understand and model these factors. Like all modernist social sciences, organization studies seek to control, predict and explain. One of the main goals of organization theorists is to develop a better conceptualization of the organizational life.

Organizations could be studied from various perspectives. Organizational analysis draws upon a number of theories in this respect. Metaphor is one such way that helps us in understanding how the organization manages itself (Morgan, 1980)3. The central thesis of this theory is that organization and management are based on implicit metaphors. Metaphors help us to understand and highlight certain aspects of organizations. For example, Morgan (1997)4 uses a very common metaphor of a machine for an organization. He states that we use the term that when things are going well we say the organization is ‘running like clockwork’, a ‘well-oiled engine’ or an ‘assembly line’. When they are not, then communication has ‘broken down’ and ‘things need fixing’. He argues that using this metaphor makes people regarded as ‘cogs in a wheel’, and attempt to quantify and measure everything. He says, “One of the most basic problems of modern management is that the mechanical way of thinking is so ingrained in our everyday conception of organizations that it is often difficult to organize in any other way.” In his book (Morgan and Video Training, 1997)5 Morgan illustrates his ideas by exploring eight archetypical metaphors of organization: Machines, Organisms, Brains, Cultures, Political Systems, Psychic

Prisons, Flux and Transformation, and Ugly faceInstruments of Domination. He highlights how various metaphors can help in understanding organizational structure and systems. Metaphors provide a ‘common definition language’ with which organizational stakeholders communicate to each other and get to the underlying reasons why something is the way it is.

Cornelissen (2005)6 highlighted the growing acceptance of metaphor in organizational theory and suggested that work should be done to understand how metaphors operate in an organization. He highlighted that locating the metaphor is the first step in reading the organization and put forward three main reasons for using metaphor as a tool for organization study:

- It provides a vocabulary which can be used to express, map, and understand a particular organizational phenomenon that otherwise is difficult to study.

- Metaphor exhibits broader meaning and are not constrained to one sense or a single interpretation, but, rather have a distinct quality of opening up new and multiple ways of seeing, conceptualizing, and understanding of organizational systems.

- Metaphors have a strong semantic quality that makes them irreducible to “non-metaphorical language.”

IMPACT OF “AKHUWAT” AS A METAPHOR ON THE ORGANIZATION

- a) Culture: Culture could be defined as the shared patterns of values and beliefs of the people that helps them understand how the organization functions (Deshpandé, Farley et al. 1993)7, while Schein (1984)8 highlights that culture could be studied at various levels like office layout, behavior of the people, dressing, stories etc. If we look at Akhuwat’s culture from the aforementioned points, we can clearly see that unlike offices of other microfinance organizations which are lavishly furnished and are located in posh areas with very high overheads, lots of cars and fanfare, Akhuwat offices are located in mosques, in small communities, with very minimum furniture. All guests are seated on the carpeted floor, there are no air-conditioners.

For Akhuwat, the association with the Masjid became a source of inspiration and strength, and supplemented the lending philosophy and methodology of Akhuwat. The centrality of the mosque in Akhuwat’s operations helped Akhuwat in achieving multiple objectives. Firstly, it helped them revive an old tradition set by the Holy Prophet (Sunnah)9 of using the mosque for social purposes. Secondly, the place and context of the mosque added a sense of sacredness, honesty, trust and responsibility. Thirdly, a vast network of mosques is spread throughout the country. The catchment area of each mosque is usually a small community of 200-300 houses. Fourthly, the aggregation of the populace at the mosque five times a day for prayers allows Akhuwat to market its cause and products without investing heavily in marketing workforce or promotional drives. Fifthly, the traditional models of group lending require one person to interact with a group, whereas for individual lending mass mobilization was the major constraint, both in terms of effort and Human Resource (HR) requirement. The use of mosque by Akhuwat reduced the effort of mobilization as well as the HR needed to manage the loan operation. Signing of the loan documents in the mosque made the document sacred and was instrumental in reducing the default rate. Moreover, since a mosque represents aggregation of a small community whose members know each other, socially and economically, it was easy to gather ‘guarantors’ for social collateral.

Centrality of the mosque in Akhuwat’s lending methodology enhanced the operational efficiency, while the effectiveness increased multi-fold. The stakeholders are meaningfully engaged through the mosque for transactions and agreements. Governance, transparency, participation and societal responsibility are best manifested. As such the mosque becomes a catalyst for socio-economic development of the community and moral uplift of the society.

The office environment gives a clear message to its community that we are not about making money and we live and practice the concept of Akhuwat. Low-cost office locations in mosques (Masjids) help them reduce their overheads and give an aura of trust and at the same time saves money in creating awareness and provides easy access to its customers. This entire system creates a culture of brotherhood. People who visit offices are impressed by the simplicity of the organization and readily buy the concept that it has to offer.

Employees of the organization also exude the same spirit of Akhuwat. Most of them belong to the area which Akhuwat is serving. They work there with zeal, a sense of ownership, and mission. They all talk the same organizational language and communicate more or less the same message. They believe in the concept of Akhuwat and are proud to be associated with it.

- Volunteerism: One very important contributor to the success of Akhuwat is volunteerism. According to Dr. Amjad Saqib, the founder and Executive Director, “In Akhuwat, we expect people to give their time and their abilities for free; the spirit of the entire organization is based on volunteerism. This is also derived from our faith, in which the principle of volunteerism is the most important part of our tradition. Every prophet is a volunteer, right from Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and the Holy Prophet (PBUH). The Prophets always looked beyond themselves to help the community socially, morally, economically, and politically. We wanted to follow the footsteps of these great prophets and adopt their methods of bringing change to the community through participation.”

Akhuwat has two types of organizational streams running in parallel: ‘hired management’, and ‘volunteer management’. The ‘hired management’ is responsible to run the operational affairs, adheres to the Akhuwat values, and has committed itself to the cause. Its untiring effort in loan disbursement and recovery, and to make the new model successful, makes it exemplary in the highly materialistic micro-finance world. Volunteers make a steering committee that not only looks after some aspect of the operations of the branch but also acts as a mouth piece, face and event organizer of Akhuwat. Most of the volunteers are well-to-do persons of that community or of the adjoining area. These volunteers join only because of the concept of Akhuwat and are not motivated by any financial or personal rewards.

- Performance: According to the audited statement of accounts of Akhuwat, the fund has crossed the 1 billion mark. Today, Akhuwat has 54 branches in 10 cities of Pakistan and has a recovery rate of 99.85%. This is exceptional by all standards. The performance of Akhuwat surpasses any other microfinance of the world in two major ways:

- It is the only micro-finance organization that takes no processing fee, late surcharge, or profit on its loans.

- It is the only micro-finance organization that has converted its borrowers into donors.

This again was made possible by highlighting the true spirit of Akhuwat as envisaged by the Holy Prophet (PBUH). The contribution achieved in some branches is enough to cover the overall operational cost.

MFI’s AND AKHUWAT: THE PHILOSOPHICAL DIFFERENCE

Akhuwat loan philosophy and portfolio differs from traditional MFIs. It offers not only micro-finance loans for entrepreneurial purposes but also provides social loans targeted to address social needs of the deserving, such as marriage loans, health loans, educational loans, and liberation loans meant to liberate people from the clutches of loan sharks. Akhuwat also distinguishes itself from other MFIs by being the first MFI which writes-off the loans if the borrower becomes physically handicapped and is unable to pay back the loan, besides providing a wheel-chair to the handicapped free of charge. Furthermore, in case of death of the borrower, Akhuwat extends support to the bereaved family and gives monetary support to cover funeral charges and provides subsistence allowance for three months if the deceased was the only earning member of the family. Akhuwat expands its donor base not by going to international donor agencies; rather it encourages existing borrowers, who have improved their economic condition through loans borrowed from Akhuwat, to participate in the uplift of their brethren and become donors.

LOAN GUARANTORS

Unlike group finance methodology adopted by conventional MFIs, where group members provide social collateral, Akhuwat gives loans to families and not to individuals and furthermore, it requires personal guarantors in order to disburse the loan. The borrower family is required to present one individual guarantor, preferably from the neighborhood. In case of failure to repay the loan, the borrower may be relaxed by extending the stipulated timeframe. Later, the guarantors are approached and reminded of their responsibility and relation to the borrower i.e., of brotherhood, and are asked to support and facilitate payment of the due amount.

CREDIT DISBURSEMENT

Akhuwat disburses loans in a ceremony performed inside the mosque which is a symbol of harmony among people where all converge regardless of caste, color and creed. The whole community is invited where first the introduction to Akhuwat, its cause, guiding principles and methodology is given. The local speakers like Imam Masjid10 and social activists also participate in such events. This helps Akhuwat in efficiently promoting its cause and helps bring in more donors as well as borrowers. The occasion is also used to highlight the social agenda of Akhuwat and an attempt is made to instill ethical values required for business.

CAPACITY BUILDING

Akhuwat also engages in the capacity-building of people by advising for business, arranging seminars, conducting entrepreneurial trainings, and distributing literature. The propagation of the social agenda at the platform of the mosque further emphasizes female education, community service, plantation, and adherence to law and ethical values. The participants of the loan disbursement events are also moved to contribute to the cause and help their brethren in need.

CONCLUSION

Although they reveal reality partially, metaphors are a strong tool to understand and analyze organizations. Akhuwat as an organization exemplifies the use of the ‘Akhuwat’ metaphor as a guiding philosophy, in both letter and spirit. In fact, Akhuwat mirrors the metaphor ‘Akhuwat’. It not only has developed its organizational and financial model in the broad interpretation of the spirit of ‘Akhuwwah’ but has also demonstrated that poverty cannot be alleviated without taking care of the feelings and wellbeing of the community. Unlike other micro-finance models, where individuality is highlighted in the name of group-lending, this model creates collectivism and brings the community together. This is the only model in the world that encourages the borrower to become a donor and take part in uplifting the overall community. The voluntary model of Akhuwat ensures that the spirit of ‘Akhuwwah’ is executed in its truer sense, in totality. Well-to-do people of the community converge to dedicate their time, energy and skills for the cause of ‘Akhuwwah’. This leads us to conclude that ‘Akhuwat’ as a metaphor has delivered to the organization of Akhuwat more than any other metaphor could have ever delivered to any organization. Moreover, Akhuwat–the organization—that embodies ‘Akhuwat’ – the metaphor— has delivered more to the world than any other micro-finance model or metaphor. Certainly, ‘Akhuwat’ as a metaphor and Akhuwat as an organization, both offer interesting insight and great promise and urge the microfinance world to rise above financial interests and look for and embody some ‘larger than life cause’ to serve the lives of the poor. While other organizations claim “we mean business,” Akhuwat claims “we mean Akhuwat.”

NOTES

1) Harper, M. (2008). “Akhuwat.” Akhuwat: Microfinance with a Difference”: Friends of Akhuwat (1) 29-40.

2) The saying narrated by Anas ibn Malik (may Allah be well pleased with him!): lA yu’minu aHadukum HattA yuHibba li-akhIhi mA yuHibbu li-nafsihi [literally: None of you believes until he wants for his brother what he would want for himself.]

3) Morgan, G. (1980). “Paradigms, Metaphors and Puzzle Solving in Organization Theory.” Administrative Science Quarterly 25(4): 605622.

4) Morgan, G. and K. I. Video training (1997). “Images of Organization.”

5) Ibid.

6) Cornelissen, J. P. (2005). “Beyond Compare: Metaphor in Organization Theory.” The Academy of Management Review 30(4): 751-764.

7) Deshpandé, R., J. U. Farley, et al. (1993). “Corporate Culture, Customer Orientation, And Innovativeness In Japanese Firms: A Quadrad Analysis.” The Journal of Marketing 57(1): 23-37.

8) Schein, E. H. (1984). “Coming To A New Awareness of Organizational Culture.” Sloan Management Review 25(2):3-16

9) Sunnah, the way Prophet PBUH used to do things. In Islamic tradition, to practice Sunnah is considered an act of high virtue and every Muslim tries to uphold Sunnah.

10) A person who leads prayers and is responsible for the mosque operations and is held in high regard by the community.

Achieving Triple Bottom Line: Sustainability, Growth and Welfare

Ather Azim Khan agencies give a large amount of money to icrofinance is now a popular form of poverty alleviation. Many international donor

Microfinance Institutes (MFIs) for poverty alleviation. The funds are given directly or indirectly to the MFIs at varying costs. Determining the right cost of financing is an important issue in microfinance as the most suitable cost of financing is likely to result in achieving the objective of poverty alleviation both in the short term and long term. Some microfinance providers prefer low cost for various reasons, which are discussed in detail in this article and others advocate high lending cost. These two viewpoints have their own reasoning and set of arguments, which require analysis and debate. This article attempts to find out the most suitable approach of microfinance with reference to Pakistan. As the economic, financial, social and political conditions are unique and the behavior of borrowers is also different in every country, so it cannot be said that one approach of microfinance will prove to be the best for all countries and all societies. The approach of microfinance that stresses the importance of existence and continuous development of MFIs argues that poverty alleviation through microfinance is linked to the existence of MFIs and if these institutions get weakened the process of poverty alleviation will slow down and ultimately stop when these institutions will cease to exist. This requires strengthening the institutes and keeping individuals i.e. poor borrower as the second preference. In contrast to this approach is the viewpoint of helping the poor and keeping them at the top of the priority list. The second approach supports helping poor not only by giving them opportunities to borrow but to give them finances at a cost lower than the market. These two approaches of microfinance are called ‘Institutionists’ Approach and Welfarists’ Approach respectively. As the names imply the first approach supports the sustainability and growth of microfinance institutes and the second favors giving low cost financing to the poor i.e. subsidized financing and it does not consider institutional profits. The two approaches are discussed in detail to compare and contrast not only the approaches but also the benefits and problems of each approach.

WELFARISTS APPROACH – OLD PARADIGM

This is now considered the ‘Old Paradigm’ as now most of the MFIs have agreed to the second approach for their better performance and long term existence. This approach is also not very popular in the world for the reason that microfinance fund providers do not approve of this approach and require the MFIs to charge high interest rates. The Welfarists’ approach sees microfinance as one of the most effective tool to help poor come out of poverty and have a sustainable life. The concept is directed towards a self-sustainable family and self-sustainable-society. The goal is poverty alleviation including women empowerment, as microfinance mostly emphasizes lending to women and involving them in economic activity, hence empowering them. This approach does not only lead to financially stronger families but also generates economic activity. However the prime objective of this approach is not to generate economic activity using microfinance; it is a byproduct and not the main product. The main objective remains helping the poor and to reduce poverty. So in the light of this approach microfinance decisions should not be made to generate or increase economic activity but to help the poor and alleviate poverty. This may or may not generate economic activity and may or may not be a financially viable proposition in all cases but it should not be stopped because of the fact that a MFI is not a financially viable proposition for a certain period of time. The approach stresses the fact that if it is not considered an act of welfare then microfinance will be discontinued in many cases. If we look at it from the ‘Welfarists’ angle it becomes extremely important that those who do it i.e. either the state or non-state players must have a good intention i.e. to help the poor. This means morality becomes an integral part of microfinance in this approach. When microfinance is offered by a bank or financial institution, formed for the purpose of making profits then it only operates when it earns profits or foresees profits in the future and in case there are no chances of profits this activity will be stopped by such banks and financial institutions.

The approach calls for subsidizing this finance and ask some outsiders to bear the cost of funds and operations to give money to the poor at a minimum rate. In this approach mobilizing savings of the poor is not the main objective. Robinson (2001) writes that savings mobilization is not a common feature of this poverty approach. So the advocates of this approach certainly do not emphasize on making profit and are not largely concerned about the issue of sustainability. The point that a reduction in the fund base over a longer period would entail that lesser and lesser people will be benefitted is not an issue in this approach. Robinson (2001) writes, “Most institutions that provide subsidized credit fail and even successful institutions following the poverty lending approach, in aggregate; can meet only a small portion of the demand for microfinance”. Morduch (2000) calls it microfinance schism and gives a split of two approaches. In the case of Welfarists the emphasis is actually placed on the number of beneficiaries rather than the profits made by the MFIs. Welfarists are more concerned about the well-being of the people than financial stability or financial sustainability and believe in giving perpetual subsidies to maximize the impact of microfinance in poverty reduction. This approach is a humanistic approach where institutions become less important and human beings become more important. The responsibility of the society towards the poor at present is more important than the probable poor of the future, hence maximum benefits should be passed to the poor at present and better strategies and policies should be formulated to make subsidies more consistent. Woller (1999) writes, “Like Institutionists, Welfarists have assumed more impact than they actually have been able to document,” which is a statement that needs empirical evidences from various parts of the world. ‘Welfarists’ believe that the ‘Institutionists’ approach is a threat to the shared objective of poverty reduction. Another valid argument of Welfarists is that if microfinance is basically to help the poor than with ‘Institutionists’ approach it would never be a tool to help the poorest of poor i.e. the destitute. If this element of subsidy and donation is added to microfinance then it can reach to that section of the poor who are truly deprived. Robinson (2001) writes that the approach of the

‘Institutionists which suggests that financial sustainability and access to financial services are more important than poverty alleviation is very strongly opposed by Welfarists. Robinson has also written that some of the best microfinance providers are Bank of Rakyat Indonesia (BRI), BancoSol in Bolivia and Association of Social Advancement (ASA) in Bangladesh.

Welfarists react very strongly to the Institutionists’ approach of making self-sufficiency the goal of MFIs and they stick to their very basic objective of helping the poor and alleviating poverty. Because of their approach Welfarists are not ready to make any compromise on their goal and they are not ready to take steps to attain financial self-sufficiency.

The question that arises is whether organizations should be allowed to undertake microfinance as an economically viable activity and make profits out of it i.e. making profits by helping the poor. As and when a microfinance bank or financial institution for microfinance will become economically unviable it will stop its operations and the poverty reduction rate will start reducing in the community.

Looking at microfinance banks we find that large funds can only be created in the government sector or in the private sector; large fund base cannot be formed unless some proper corporate structure is given to these organizations. This corporate structure on one side is helpful to have a large fund base but on the other side increases the cost of operations and eliminates the human element from the organization i.e. to help the poor and so it becomes more mechanical. In Pakistan some NGOs have changed their status and converted into banks such as Agha Khan Rural Support Program – AKRSP into First Microfinance Bank and Kashaf Foundation into Kashaf Bank. These bank models are primitive and these banks operate in somewhat the same way as commercial banks.

Many experts believe that micro businesses profits margins are very high and so it is possible to pay very high interest rates on micro loans (Woller, Dundord, & Woodworth, 1999). It is something that seriously needs to be considered and brought into the limelight for discussion. It is said in the USAID report of 2005 that most of the microfinance organizations charge very high interest rates all over the world but in Pakistan the interest rate charges are very low and so the MFIs in Pakistan are not self-sustainable. It is generally accepted that all MFIs like other business organizations should be able to make enough profits to cover their cost of operations and cost of borrowing otherwise these organizations will not be self-sustainable. There are several questions that need to be asked regarding this approach, some of which are mentioned below:

- Why are funds given at high rates or at the same rates to MFIs and by MFIs to the poor borrower?

- Why are the operating costs high, even higher than other profit making organizations, when the default rate is almost negligible or in some cases much less than the commercial borrowers?

- Why is philanthropy not considered as one of the source of providing funds to MFIs?

- Why do not governments subsidize lending in case of microfinance?

- Why are benchmarks not set for operational expenses of MFIs?

- Does every poor person borrow microfinance for doing business?

- Is every poor borrower capable of doing business?

- What if there is loss?

- Are profit rates in different micro businesses known?

- What are the other dimensions of microfinance apart from micro loans?

- How are returns taken or calculated on other forms of microfinance i.e. projects of health, sanitation, insurance etc.

Marguerite Robinson in her book ‘The Microfinance Revolution’ has given the theory of subsidy free microfinance, as in long term subsidies cannot continue and are reduced or eliminated. Robinson calls it the “old paradigm” where poverty alleviation microfinance programs are highly subsidized and were not successfully run due to high losses. She contrasts it with what she calls the “new paradigm” where financial services are offered in a cost effective manner i.e. making financial institutions (MFIs) self sustainable. This new paradigm requires charging high rates to the poor as they can make good profit of the money borrowed. There is no difference of opinion on the issues of transparency, efficiency, maintaining the link between cost of credit and interest rate, mobilizing savings and providing incentives to the employees but the issue is why MFIs should be self sustainable? The society as a whole and the governments specifically should always contribute for the betterment of the poor and deprived of the society and this contribution should always be available. Robinson (2001) wrote that arguments given in favor of the old paradigm need to be analyzed and readdressed. The arguments are the following:

- Lower income people need credit for productive inputs

- Because their incomes are low, they cannot save enough for the inputs they need

- They also cannot afford to pay the costs of the credit they need

- Lower-income people are generally uneducated and do not trust banks; they either do not save, or prefer to save in nonfinancial forms

- If such people are to save in banks, they need to be taught financial discipline

INSTITUTIONISTS APPROACH

The other side of the picture is the ‘Institutionists’ approach. This approach is very much tilted towards the building of sustainable institutions instead of depending on ‘individuals’, philanthropy or temporary funds. Institutions are long lasting and sustainable and in the long run can support the cause of poverty alleviation. Institutes are not run at the will or desires of individuals but with given norms, principles and rules and are governed by regulatory authorities and so it is difficult to misuse the funds available in these institutes. It is important to build institutes rather than stressing on the need of philanthropy. For an institution to be sustainable it is very important that the institution generates enough revenues that make up its costs i.e. borrowing cost, operational cost and capital expenditures.

Borrowing cost is associated with borrowing money from a lender. This comprises mainly of the interest paid on the amount borrowed and includes other related cost to process the loan. In most cases the funds provided by international and national agencies are at relatively lesser rates than the rates charged for other types of financing. Borrowing cost is to be generated by the organization every year either from charging high interest from the poor or by taking donations or further loans. Operating cost is the second head that needs to be paid by an MFI on regular basis. These costs depend upon the setup of the organization and include the salary of employees, utilities expenses, travelling cost, repairs and maintenance, depreciation etc. Capital expenditure are the cost to be incurred on the two approaches of microfinance i.e. ‘Welfarists’ Approach and Institutionists’ Approach and are based on two theories:

‘Economic Theory’ and ‘Psychological Theory’.

ECONOMIC THEORY OF MICROFINANCE

Economic theory of microfinance treats microfinance institutions as an infant industry. It is said that the gist of the economic argument is that success in any business venture, including MFIs, is determined by the entrepreneurs’ ability to deliver appropriate services profitably. However, studies conducted in different parts of the Third World show that there are no successful MFIs by this definition. At best, some MFIs cover their operating costs while some of the better known among them are able to cover a part of subsidized cost of capital employed. This situation suggests that the MFIs are not likely to become financially viable in the long run.

The infant industry argument in economics is based on the concept of protectionism i.e. policies or doctrines which “protect” businesses and workers within a country by restricting or regulating trade with foreign nations. The infant industry argument as first given by Alexander Hamilton in 1790, is that nascent industries because of their smaller size do not enjoy economies of scale and so have high costs as compared to their competitors and so they need to be given protection in the initial phase of their business until they achieve economies of scale and become competitive. This justifies measures of protectionists in the scaffold of free trade theory in its classical sense. This infant industry argument is applied to microfinance industry to help it in the initial stages until it reaches the level where it can survive on its own and sustain itself. This means MFIs should be provided low or cost free funds, subsidies in operating costs, long term funds and other benefits to help them survive in the market for a certain period of time till they achieve economies of scale. Elahi (2004) suggests that critical evaluation is needed to judge the academic virtue of microfinance theory. The Economic view is supported by the main theorist of capitalism; Adam Smith who stressed that prosperity depends upon the progressive creation of private wealth. Smith (1776) emphasizing the point that the main source of creation of private wealth is the self-interest says, “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their self-interest; we address ourselves not to their humanity but to their self-love and never talk to them of our own necessitates but of their advantages”.

Thomas Hobbes, who is a diehard materialist, gives his view of every economic activity as nothing but making profit and self-interest. He calls human beings as living machines and says that these machines move only by natural passions i.e. appetites and aversions. He further defines appetites as innate and social; the biggest social appetite he considers the desire for power. He considers the human beings are propelled only by self-interest, which may be the fear of extinction that leads to law and justice (Levy, 1954).

Coming back to the Infant Industry argument sprouting from the protectionist’s argument in mercantilism, which was developed to accommodate mercantilist feelings inside the Adam Smith’s structure of liberal economic theory, it is this argument which is invoked to develop microfinance in the Third World.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY OF MICROFINANCE

Psychological theory of microfinance makes a distinction among professional money lending and microfinance and presents microfinance providers as, “social consciousness driven people”. The psychological component of the micro credit theory – known as social consciousness-driven capitalism – has been advanced by the most ardent promoter of micro finance, Dr. Muhammad Yunus. Yunus (2008) argues that a species of profit-making private venture that cares about the welfare of its customers can be conceived. In other words, it is possible to develop capitalist enterprises that maximize private profits subject to the fair interests of their customers. Analysis of this theory reveals that it is based on the understanding of capitalistic approach, an approach where profit is the ultimate objective and as said it has a somewhat selfish nature. Investors also have the profit motive and funds are available when the required rate is offered to them. This does not consider that element which provides funds for reasons other than making profit or getting high returns. In the present age where social responsibility is also associated with corporations, an additional objective of social returns is also added to profit making. Considering this, we can differentiate entrepreneurs into three categories. The first group consists of traditional capitalists who mainly maximize financial returns or profit, the second group is of philanthropic organizations e.g. traditional microcredit NGOs and public credit agencies that mainly maximize social returns and the third group consists of entrepreneurs who combine both rates in making their investment decision under the additional constraint that financial return cannot be negative. The third group consists of entrepreneurs who are to be treated as socially concerned people, and microfinance, which is to be treated as a social consciousness-driven capitalistic enterprise (Elahi & Danopoulos, 2004).

Yunus (2008) writes that these socially motivated people can bring a change in the society as they can do many activities of public welfare while making profit. He includes health care, education, training, financial services, energy ventures, old age homes, recycling enterprises or marketing of products made by poor. Yunus (2008) suggests that this system can replace the current ruthless capitalistic system where some are winners and more are losers. He suggests that this system does not demand charity from individuals, companies or public sector but it demands doing business with the poor for profit. In the words of Steven Covey this leads to a Win-Win situation where the entrepreneur does not have to sustain a financial loss to help the poor but rather brings him on board and makes him self-sustainable. Yunus (2008) explains the weakness of the theory of capitalism as apparent from the inconsistent views of Adam Smith, which are very much contradictory to each other.

Adam Smith who on one hand gave the main theory of capitalism also talks about the psychological aspect in his book ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments’. The interesting point is that this book was published many years before the ‘Wealth of Nations’, so it may contain a view point which may be altered by Adam Smith himself. Smith (1759) thought that the real source of moral judgement lies in the conception of sympathy, as written by him:

“How selfish so ever, man may be supposed, there are evidently some principles in his nature, which interest him in the fortune of others, and render their happiness necessary to him, though he derives nothing from it except the pleasure of seeing it. Of this kind is pity or compassion, the emotion, which we feel for the misery of others, when we either see it, or are made to conceive it in a very lively manner. That we often derive sorrow from the sorrow of others is a matter of fact too obvious to require any instances to prove it; for this sentiment, like all other original passions of human nature, is by no means confined to be virtuous and humane, though they perhaps may feel it with the most exquisite sensibility. The greatest ruffian, the most hardened violators of the laws of society, is not all together without it.”

Smith in his views about the psychological approach negated Thomas Hobbes who conceived human beings as living machines. Hobbes wrote, “The human heart is simply a spring; nerves are nothing but a complex system of strings; and joints are just wheel which give motion to the whole body.” According to Adam Smith there is a fundamental virtue in human nature. He used the word sympathy in describing the moral judgment of human beings. Smith says that the word sympathy includes two kinds of moral judgment i.e. one is the propriety of an action that determines right or wrong and the second is an action’s merits or demerits that determines praise or blame. The conflicting views of Adam Smith in his two books ‘The Wealth of Nations’ and ‘The Theory of Moral Sentiments’ are stated in the literature as ‘Das Adam Smith Problem’, this is an allegation that the two cannot be compatible.

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE TWO THEORIES AND THE CONTRADICTIONS

The combination of the two theories creates disbelief about the theory of microfinance. Capitalism is mainly driven by selfishness and so social consciousness or sympathy cannot be the motivating factor to do business in capitalistic economies. As microfinance is also motivated by same factors so in capitalistic economies it is not possible to successfully do micro financing without the profit incentive.