Interest Free Microfinance And Impact On Poverty Alleviation

Europe Economics is registered in England No. 3477100. Registered offices at Chancery House, 53-64 Chancery Lane, London WC2A 1QU. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information/material contained in this report, Europe Economics assumes no responsibility for and gives no guarantees, undertakings or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or up to date nature of the information/analysis provided in the report and does not accept any liability whatsoever arising from any errors or omissions.

© Europe Economics. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism or review, no part may be used or reproduced without permission.

Interest free microfinance and impact on poverty alleviation

Interest free microfinance and impact on poverty alleviation

1.1 The rise of microfinance

The inception of microfinance, as is known today, began with an experiment conducted by a professor in Bangladesh in 1976. To help the poverty stricken and flooded village of Jobra in Bangladesh, Professor Mohammad Yunus, a lecturer of economics at Chittagong University, lent $27 each to a few women as working capital without interest. What surprised him was the fact that these women invested this money in their modest commercial enterprises and were successful. They came back thanking him and returned the borrowed amount. Thus, this small experiment started what was to become a global revolution in microfinance.

As time passed, microfinance was perceived as the answer to the world’s poverty problem. World leaders were thrilled around the globe and uptake of microfinance boomed amongst institutions and non-government organisations (NGOs) with billions of development funds coming through to eradicate poverty and help the cause of female empowerment. So much was the enthusiasm and confidence present in the scheme that the United Nations (UN) and the World Bank declared 2005 as the year of microfinance and Yunus and Garmeen bank were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for starting this revolution to create economic and social development. However, unfortunately, the charm and enthusiasm faded out within the next five years as the claims of poverty eradiation and female empowerment were challenged and could not be corroborated.

Moreover, incidences of exorbitant interest rates in excess of 40 per cent being charged by the institutions were revealed. The presence of high interest rates is justified from an economic perspective. As these borrowers do not offer sufficient collateral and nor do they signal their ability to successfully repay their loans though credit ratings and due diligences as big businesses do, the lenders are faced with the problem of adverse selection. That is, in order to ensure their profitability, lenders do not have a choice but to charge high interest rates to all the borrowers with the effect that the good borrowers are subsidising the bad borrowers who are unlikely to repay the debt. However, this regrettably fails to deliver the objective of poverty alleviation.

Where lenders could not extract the interest and principal payments from borrowers who had not been successful with their commercial ventures and were unable to pay the loans, they used harsh means including public shaming rituals. Whole villages in India defaulted on their debt and were forced into a worse poverty that greatly damaged their social capital. There were instances of suicides by borrowers who had defaulted. According to India’s National Crime Records Bureau, more than 87,000 farmers committed suicide between 2002 and 2006 because of failing harvests and huge debts. These instances made governments realise the social damage being done by the microfinance system which was, at worst, exploiting the poorest, neediest members of the society.

All in all, reports suggested that microfinance had not helped achieve its initial goal of eradicating poverty. Whereas it had provided support to some entrepreneurs saving them from unregulated money lenders (who offered even worse interest rates) and had led to consumption smoothing, its overall objective had not been achieved. Also, a comprehensive study of 13 micro credit schemes in Asia, Africa and South America unanimously indicated that the benefits of the micro credit schemes under study varied for different income classes – the upper and middle income poor tended to benefit more than the poorest of the poor (Hulme and Mosley 1996). At worse, interest-based microfinance had worsened the problem by submerging the poor in repeated rounds of debt.

1.2 Interest free microfinance vs conventional microfinance

Given the failure of conventional microfinance to alleviate poverty, interest free or charity based microfinance models have gained popularity in developing countries and especially in Islamic countries where the concept of interest free Islamic finance products appeals to the public, in general. Some of the countries where interest free microfinance has gained popularity include Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Bosnia, and Herzegovina and some African countries.

Interest free microfinance provides a good alternative to conventional microfinance by providing collateral free and interest free loans to the lender. The provision of funds (through interest free or interest based lending mechanism) prompts individuals to invest some if not all of the loan amount in commercial ventures. Unfortunately, due to the extreme level of poverty prevalent in the developing and least developed economies and the lack of public services such as health and education, some of the loans are likely to be spent on household consumption. Despite this, microfinance has a higher potential than charity to make a long lasting impact on poverty alleviation and to enable people to be self-reliant, as it involves an element of trust in the potential and capabilities of people to help push themselves out of poverty.

1.3 How does the interest free microfinance model work?

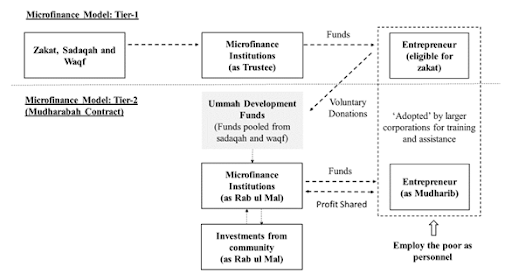

There are four main models of interest free microfinance, as well as another unique model particular to Akhuwat in Pakistan which is slowly gaining popularity in other countries such as Afghanistan. It is described in detail in the section below. The four main models are:[1]

Grameen Bank Model (Group Lending): The model operates on the basis of group lending where members of the group act as guarantors of each other and thus provide collateral through this mechanism. The use of group members as collateral minimises the risk of default by one group member as he knows he will not be able to secure finance in the next round were he to default on his payments. This is the most popular interest free microfinance model implemented successfully by the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh.

Village Bank Model: The village bank model consists of a group of approximately 30 individuals established by the microfinance institution (MFI) which injects capital into the group for forward financing[2]. The repayment of loans which have been lent forward by the group members amongst themselves takes place on a weekly basis and after four months all the loans along with the profit are returned to the MFI. Subsequent loans depend on repayment by the village bank and the size of these loans depends on the profit or savings returned to the bank. In this instance, peer pressure leads to a lower risk of default and also encourages greater savings to enjoy bigger loans in successive periods. This may also lead the village bank to become self-sustaining by accumulating internal capital.

Credit Union: Credit unions are non-profit committees formed by a group of people who have a common bond. The union is controlled by the members themselves who offer a range of services from saving to credit extension and recovery. However, credit unions are generally linked to some body that supervises, provides training, and monitors performance.

Self-Help Groups: Self-help groups are groups formed by people from similar income levels coming together to help each other. The group members pool the money together and extend credit to whoever is in need.

These groups can also seek external funding if need be. Members of the group decide among themselves about terms and conditions of all products/services they have agreed to offer to each other through this arrangement.

1.3.1 Akhuwat model

Akhuwat is an interest free microfinance institution in Pakistan that works on a unique model of brotherhood where it believes that people should help each other and that charity is better than “qard-e-hassna” (an interest free loan). The model entails a zero interest rate and voluntary contributions. It uses the value of social collateral whereby members of a group act as collateral for each other, decreasing the risk of default.

Akhuwat works on the basis of contributions from civil society and voluntary contributions from the borrowers, who are encouraged to contribute any amount they wish in addition to instalments for payment of the principal. It does not depend on international funding; instead it uses the spirit of volunteerism and the tradition of giving. It has been operating in Pakistan since 2001. Since then, it has established 500 branches across the country and has been instrumental in helping more than 1.3bn families to become self-reliant.[3] The success stories of these people bring hope to those still in need of help.

Perhaps the most interesting insight into the Akhuwat model is that the voluntary contributions from the borrowers have resulted in implicit interest rates of around 4.5 per cent. Though these rates are not as high as the interest rates charged by conventional South Asian microfinance institutions of around 15-20 per cent, they are not inconsequential either.[4]

According to a study conducted by the University of Kent, individual borrowers tend to offer high contributions at the beginning of their loan cycle but the frequency declines towards the end of the cycle. Also, voluntary contributions made in a loan cycle correlate positively with repeat borrowing for both first and second time borrowers.

On the other hand, in the case of group lenders, contributions start out as small and increase towards the end of the loan cycle. This is because groups aim to secure repeat loans from the organisation in the future and hence try to incentivise this with higher contributions. Thus, there is evidence that voluntary contributions are being rewarded by the institution through the provision of repeat cycle loans to the borrowers, and that the borrowers are also strategically timing these voluntary contributions through their loan cycle to maximize impact.

In addition to being a way of seeking repeat loans, these voluntary contributions also act as a signalling mechanism to separate low quality from high quality borrowers, especially in joint liability borrowing arrangements. Voluntary contributions by the poorly performing group are on average higher than those of a high performing group. Some borrowers in a poorly performing groups contribute more than others and contribution from each borrower is received separately from the loan instalment which is only strictly accepted on behalf of the group. This shows that good quality borrowers are signalling their quality independent of their joint liability groups so as to ensure that the provision of successive loans is not denied to them in the future even if it is denied to other members of the group.[5] This enables the organisation to provide repeat loans to these good borrowers without having to incur the additional costs of identifying borrower quality. Moreover, the contributions can also provide some financial relief to the organisation without burdening those members of the group who are facing difficulty in paying their loan instalments.

Through this model of zero interest and voluntary contributions, Akhuwat has managed to impact millions of lives and continues to carry forward its mission of alleviating poverty by empowering socially and economically marginalized families through interest free microfinance and by harnessing entrepreneurial potential, capacity building and social guidance.

1.4 Impact on poverty alleviation – evidence from emerging economies

While interest-based microfinance has led to significant disappointment over its failure to eradicate poverty, interest free microfinance has fared better than its conventional counterpart. According to Chowdhry, 2007, despite their existence for a short span of time, interest free or Islamic MFIs have been performing better than the traditional or secular MFIs in the field of resource mobilization and poverty alleviation.[6]

A study comparing Islamic or interest free microfinance with conventional microfinance in Bosnia and Hergzovia suggests that interest free MFIs are more oriented towards the socially and economically disadvantaged than conventional interest-based MFIs, especially with regard to the cost of loans, approved grace periods, grants, flexibility in the event of repayment failure, and targeting the most marginalized groups.[7]

Another study in Indonesia examines the effect of Islamic microfinance on poverty alleviation and environmental awareness. It states that in all the areas, whether it is agriculture, forestry or marine, the MFIs were able to contribute to the financial well-being of the economy. Business development as a result of receiving credit from the MFIs occurred in all of the three regions, and borrowers, net profits, income from crops and off-farm activities increased. Capital to spend on durable good assets and agricultural inputs also increased, which ultimately resulted in increased profits and better living conditions for the farmers. However, the study states that interest free MFIs were not successful in raising environmental awareness among the borrowers, possibly because investment in eco-friendly projects was costly and risky and the interest free nature of Islamic MFIs meant they were not too keen to provide funds for high risk businesses. By contrast, conventional MFIs fared a lot better than their interest free counterparts in terms of awareness related to environmental issues.

According to the study by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 2012 on Bangladesh, Islamic microfinance was relatively more successful in reducing poverty than conventional microfinance.[8] What contributed to its success were the interest free financing options and the flexible loan repayments that enabled borrowers to manage their finances well and not to be forced into bankruptcy or selling their capital goods to pay the loan instalment in times of financial distress. It further states that interest free MFIs had greater borrower penetration than conventional MFIs due to the diverse and lucrative nature of funds available, such as charity donations which were the distributed amongst the poor as interest free loans. On the other hand, conventional MFIs had relatively little impact in terms of poverty alleviation because of their dependence on interest income for sustainability and the lack of alternative sources of funds.[9]

Thus, evidence suggests that interest free microfinance has been more successful in terms of poverty alleviation and self-sustainability than interest-based microfinance. However, despite the strong demand for Islamic microfinance products and services, the growth of this sector has been slow. This is mainly due to the fact that Islamic microfinance services are generally provided by NGOs who may not possess adequate technical expertise or funding to ensure proper implementation and sustainability in servicing the very poor. By contrast, the Islamic commercial banking sector, which provides Islamic products to the non-poor, has seen tremendous growth in the past three decades.

+effect+on+poverty&source=bl&ots=wkQw8TDQc8&sig=iSBX5n3rk–

A53BtQnJR4VEjJ7aE&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJy5vErsvNAhXiC8AKHWNED744ChDoAQg6MAQ#v=onepag e&q=interest%20free%20microfinance%20and%20effect%20on%20poverty&f=true.

[1] Ch11, “Models of Microfinance”. http://www.gifr.net/gifr2013/ch_11.PDF.

[2] Forward financing means that the group members, after receiving the capital from the MFI, lend to other members of the group.

[3] Mahmud, M. (2015). “Microcredit with Voluntary Contributions and Zero Interest Rate – Evidence from Pakistan” https://www.kent.ac.uk/economics/documents/research/papers/2015/1513.pdf.

[4] Mahmud, M. (2015). “Microcredit with Voluntary Contributions and Zero Interest Rate – Evidence from Pakistan” https://www.kent.ac.uk/economics/documents/research/papers/2015/1513.pdf.

[5] Chowdhury, M. A. M. (2007). The Role of Islamic Financial Institutions In Resource Mobilization and Poverty Alleviation in Bangladesh: An Empirical Study of Rural Development scheme (RDS) of Islamic Bank Bangladesh Ltd.

(IBBL), presented in International Seminar on Islamic alternative to Poverty Alleviation: Zakat, Awqaf and Microfinance, Jointly sponsored and organized by IDB Jeddah, IBBL Dhaka, & IERB Dhaka, Bangladesh, April 21-23, 2007, pp.1-20.

[6] Hamad, M. & Duman, T. (2014). “A Comparison of Interest-Free and Interest-Based Microfinance in Bosnia and Herzegovina” http://www.academia.edu/9945122/A_Comparison_of_Interest–Free_and_InterestBased_Microfinance_in_Bosnia_and_Herzegovina.

[7] UNDP (United Nation Development Program). 2012. “Poverty reduction: Scaling up Local Innovations for Transformational http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Poverty%20Reduction/Participatory%20Local%20Development/Ban gladesh_D10_web.pdf.

[8] Effendi, J. “The role of Islamic microfinance in Poverty Alleviation and Environmental Awareness in Pasuruan, East Java, Indonesia”